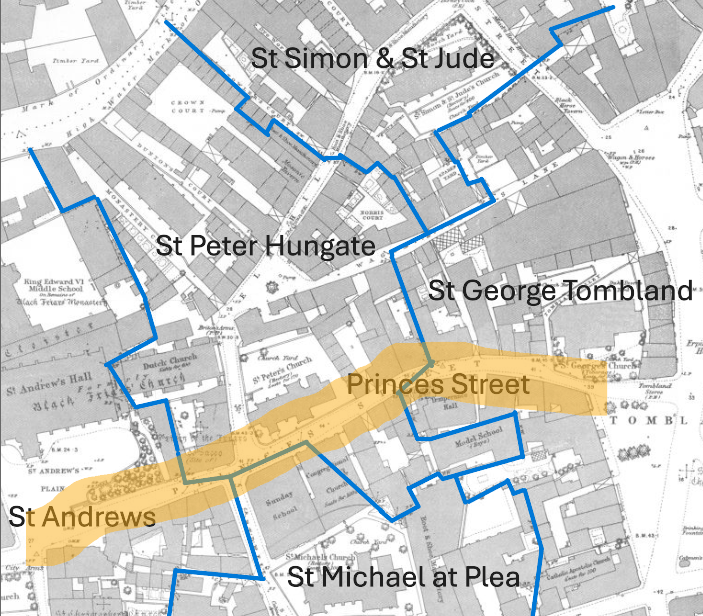

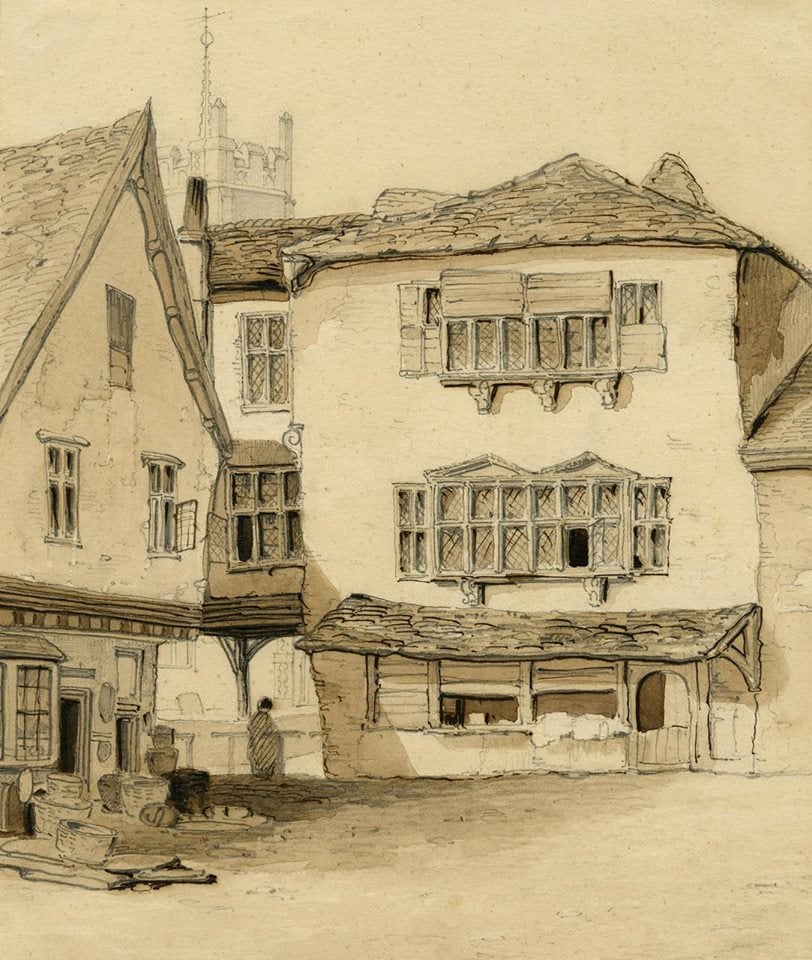

The two public houses in Princes Street were frequently in trouble with the law for breaching licensing conditions throughout the second half of the 19th century, at the same time that the Congregationalists and other non-conformists active in the Temperance movement expanded their presence in the street.

Joseph Hewing (1811-1877) became the licensee of the Plumbers Arms (20 Princes Street) from 1846, through to 1875. John Hewett, a self described Radical, ran The Coopers’ Arms at what is now 13 Princes Street, next door to the Congregationalist chapel and temperance hall. By 1872, a further outpost of the temperance movement, a British Workman’s coffee house, had opened next to the Plumbers’ Arms.

Joseph Hewing

Hewing married Jane Small of Ireland in 1833, in Bunwell, Norfolk. It seems they did not have any children, and the census of 1851 only shows the couple and some lodgers – various soldiers from the 98th Regiment of Foot and three young women – Elizabeth Hales, a 23 year old dressmaker, Hannah Catchpole, a 20 year old shoe binder and Elizabeth Hunt, a 23 year old dressmaker and her 3 year old daughter, also named Elizabeth Hunt.

The 1851 census also included a tally of churchgoing, which revealed that Congregationalist chapel on Princes Street had capacity for almost a thousand seated and held Norwich’s third largest morning congregation (573 with 191 children) and second largest evening congregation (452).

Assault

In 1847, Joseph Hewing “alias Whitehead” charged Lucy Browne with having been concerned in stealing a watch and some money from an old pensioner who had been drinking with a female in Hewing’s house, after which he was robbed. The watch was afterwards given to a boy to take to the station house, where it was detained.

A few weeks later, Hewing and Browne were at a house in Red Lion Street, when they “had a few words and Hewing struck her.” She went for a police officer but upon her return Hewing charged her with having been concerned in the robbery, and instead of being taken into custody himself for the assault, he gave her into custody. She was taken to the station house, when Hewing most positively swore she was the thief. It was afterwards proved she was not the party, and ”a charge of assault was preferred against Hewing,” which Lucy Browne “clearly substantiated.”

The Magistrates, after strongly reprobating the conduct of Hewing, fined him 10s and 10s 6d costs for the assault. In default of payment he was committed for twenty one days to the House of Correction. [1]

Jane, Joseph’s wife, died in 1855 at the age of 42 and was buried at St George Tombland. Joseph then married Sarah Mayes (1827-) at St George Tombland, in 1857.

The Plumbers’ Arms continued to attract attention in the wrong way. In 1859, George Olley, a married man, accused Archibald Maltman of assaulting him in the Plumbers Arms on the 12th March, arguing about money and a girl. Both were lectured severely and the landlord cautioned. Later that year, in July, William Browne, a 21 year old shoemaker was charged and found guilty of stealing three brass candlesticks from the landlord, Joseph Hewing.

Hewing’s licence was renewed in 1859 but with clear reservations about character of the house and concerns that it might be operating as a brothel.

Hewing managed to stay out of the news for the next couple of years and in the 1861 census he is recorded as “John” Hewing, living at the Plumbers Arms with Sarah and a lodger, Joney Wooton, an agricultural labourer.

The semblance of respectability did not last long. In 1862 Joseph Hewing was refused a license and admonished for allowing prostitutes to assemble at his house. He reapplied in 1863 but the magistrates refused the application again. He seems to have finally regained his licence, or moved to another premises to do so, as in 1865 Joseph Hewing is noted as being “a beer house keeper of Redwell Street” in a court hearing of an attempt to steal money from his till.

In 1869 the congregationalist chapel on Princes Street was rebuilt, to designs by a non-conformist architect, Edward Boardman.

One of the most improbable stories that was ever told in a Court of Justice

The very next year, Hewing was back in the news again. Ellen Chapman (28) a prostitute of Sardinian Court, St Stephen’s and William Fairweather (51), shoemaker of Heigham were charged with stealing £64[2] from him.

Hewing was near the Golden Ball public house, where he met William Fairweather, who asked him where he was going and on his telling him “anywhere where he could get a pint” the prisoner took him to a house in Sardinian Court, where Hewing gave him 6d to get a half a gallon of beer. When he came back, they sat smoking and drinking the beer. Shortly after this, another half gallon was ordered, and the female prisoner then came in and he and Fairweather played a game of cards.

When they had finished playing, Hewing went upstairs to count his money and found he had £63 in gold, which he returned to his purse and put in his pocket. When he came downstairs, he gave another 6d for more beer and at the same time a shilling for the use of the room. After drinking the second lot of beer he felt dizzy. Out of the first half gallon he only drank twice, and the same quantity the second time. Fairweather went for the beer and “both partook of it.” After he became drowsy, Fairweather told him to go and lie down, and he would call him at eight in the morning.

Hewing went upstairs and found when he woke up at seven the next morning, that he was sitting on a chair with his head resting on the bed. There was a little girl in the room. On feeling for his purse he found it was gone; and on going downstairs neither of the prisoners was there, or any other person in the house. On reaching the street he saw a policeman to whom he communicated his loss.

In answer to the Bench, Hewing said the reason he gave a shilling for going upstairs was in order to count his money without being observed. He had had two half quarterns of gin previous to meeting with Fairweather at the house where he had sold his pony and cart that evening.

Cross examined by the female prisoner he responded: “I did not go upstairs with you. I did not, after I had given you some silver, offer you four or five pounds to do what I liked with you.”

Police constable Bacon said that after Hewing had approached him he went in search of the two prisoners, whom he found together in an unoccupied house in the Pipe Burner’s Yard, St Stephen’s. He asked Ellen Chapman if she had any money about her and she handed him six sovereigns, saying they had been given to her by the man for a certain purpose. The policeman heard more money “jinking in her pocket” and she said that was her own. Fairweather handed over a half sovereign and some coppers saying it was all he had. Both were then taken to the station. The policeman said that he had known Chapman for five or six years and that after taking them to the station he went to her house, where he found a purse containing £40 in sovereigns and half sovereigns and also a phial labelled Laudanum – poison.

The defending lawyer contended that Hewing’s story was one of the most improbable stories that was ever told in a Court of Justice and that the appearance of the prosecutor was sufficient to convince the jury that he was not speaking the truth, that he preferred going with the female prisoner instead of being in bed with his wife at home.

The jury nonetheless convicted the prisoners and the Deputy Recorder remarked that the evidence was clear and he had no doubt they had drugged Hewing to obtain the money. He hoped the sentence would be a warning to them, but added that he was afraid they were too far gone to be reformed. Chapman and Fairweather were sent to prison for eighteen months with hard labour.

The British Workman coffee house

The 1871 census shows that Hewing was back at the Plumbers Arms, with his wife Sarah, but no lodgers.

A year later, Philip Impson moved into 22 Princes Street next to the Plumbers Arms and opened the British Workman coffee/public house. The British Workman movement had started in the 1860s with the aim of establishing alcohol-free public houses for working men.

Impson was a Quaker and active in the temperance movement. Before moving to Princes Street, Impson had been running a bakery in King’s Lynn in the 1860s after which he moved to Heigham, Norfolk, where he also ran a bakery.

As well as serving “a cup of coffee for 1d, a cup of tea 1 ½ d, a cup of cocoa, 1 ½ d, a rasher of bacon 2d, unadulterated bread, eggs and butter, ginger, peppermint and lemon syrups, noted horehound and ginger beer &c.” it had a club room used for meetings, singing and phonetics classes, readings, recitation and bible reading classes.

In 1872 Hewing was summoned for allowing beer to be drunk in his house at unlawful hours on Sunday night. Evidence was called to prove that the men in the house were relatives of the landlord, whose wife they were visiting on account of her illness, so the magistrates dismissed the case.

Hewing’s widow takes over

This was the last time Hewing appeared in the press, although he is shown on the 1873 electoral register as occupying a house on Prince’s Street. He died in February 1877 at the age of 66 – “greatly respected by all his friends”. He left effects of under £100.

His widow Sarah continued to run the Plumbers Arms, in a similar fashion it would seem, to Joseph, after his death. In the 1881 census she is recorded as living with Robert Wigg, 27, her nephew, Sarah M Wigg, 29, her niece, Alicia L Mayes, 19, a dressmaker and Ellen Grand, a servant, 17.

In July of that year she was summoned for allowing her house to be used as a brothel. Detective Barlow had watched the Plumber’s Arms on several occasions and saw 24 men and 23 women, some of whom were prostitutes, enter the premises between 2pm and 8:30pm. Their neighbours, Philip Impson of the British Workman and Mr Dawson deposed to the noise and turbulence not infrequently taking place at the house, the latter deposing to the fact that this had been the state of things for the last 25 years. Sarah Hewing was found guilty and in default of payment, was sent to prison for two months and the license was forfeited. This precipitated the sale of the property:

For Sale by Auction Wednesday 3rd August 1881, a Freehold property lately known as the PLUMBER’S ARMS. Easily convertible into Trade Premises. In the occupation of Mrs. Sarah Hewing and containing Bar and Tap-room, Snuggery, two Sitting-rooms, passage with access to the Yard, leading to Waggon and Horses Yard; Scullery, Wash-house, Privy, Coal-house, back passage to Garden, formerly used as a Skittle Ground; also Privy. On the First Floor, Landing, front Sitting-room and five Bed-rooms. On the second floor, Landing and two Bed-rooms. Also a Two-stalled Stable, with Hay Loft over and Cellar in the Basement situate adjoining, now in the occupation of Mr Furse.[3]

After the sale of the Plumber’s Arms, Sarah went to stay with her sister-in-law in Corpusty, where she died in 1884, at the age of 65.

The temperance movement in the 1880s

Jeremiah James Colman MP, a nonconformist from the Colman’s mustard family laid the foundation stone laid for new lecture hall and Sunday School rooms on Princes Street in 1879.

Two years later, a Temperance Hall opened in the room previously used by the Prince’s Street congregation as a school – purchased and redecorated by the Norfolk and Norwich Temperance Society.

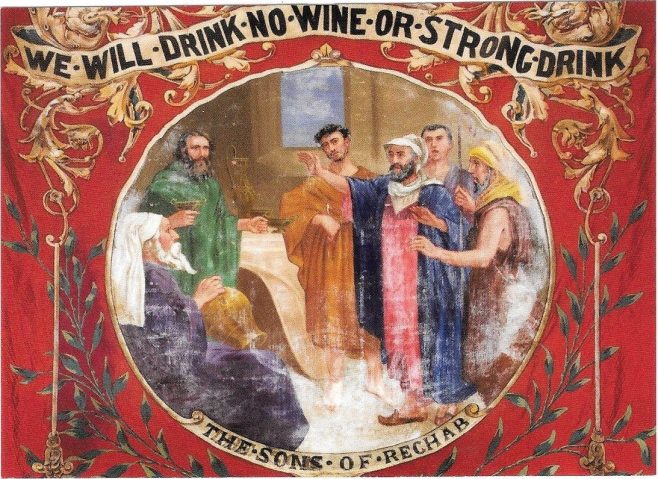

Impson continued to run the British Workman in the 1880s, appearing in White’s History, Gazetteer and Directory as the “proprietor of a refreshment and reading room (British Workman No. 1)”. He also provided refreshments for those who met at the Temperance Hall, such as the Independent Order of Rechabites, a temperance society providing insurance for working men.

Impson’s oldest daughter Catherine married Samuel Scarlett, an insurance agent for the Rechabites in 1874.

In the 1891 census Philip Impson and his wife Charlotte were living at what was then 31 Princes Street (now 22) with their daughter Mary. Philip is described as a baker and Mary as a mission worker and preacher. Their son James was also working as a baker, in St Pauls, Norwich.

By 1892 Impson was living in Swansea Road, but continued to own the coffee house premises at 31 Princes Street, until 1893, when it seems he sold 31 to the Bretts, who were living at what is now number 24. He then moved to St Mark’s Villas on City Road, where he died in 1902 at the age of 77.

[1] Norwich Mercury, 30 October 1847 p 3

[2] Around £10,000 in current day value.

[3] Norwich Mercury, 30 July 1881 p 8